South Deccan Archaeology Research Foundation

South Deccan & The Nation's Past

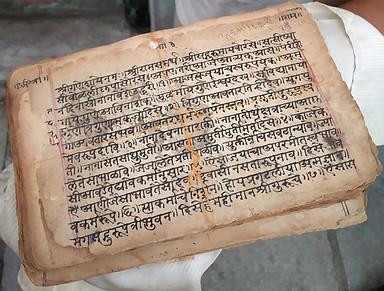

Many of the structures and sites in the North are not well preserved due to repeated incursions there. The associated texts such as Sthala Puranas (narratives about a particular place) have also been lost or are incomplete due to the same reason. The Southern part of the Deccan, which consists of the states of Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu and Telangana have been relatively less disturbed by the ravages of time. The South thus has more “material culture”, better preserved and associated Sthala Puranas. Besides the Sthala Puranas, numerous texts from the South and also from the North have been well preserved in South India.

“Material Culture” is a technical term. In the realm of archaeological surveys, “Material Culture” refers to architecture, inscriptions, and images (statues, murals, etc.). “Material Culture” helps us understand the past by deciphering the contents of inscriptions and dating the images. The architecture of temples gives us pointers about when the elements of the temples were built & by which dynasty. Architecture & iconography (pertaining to images) of dynasties have their own unique style and hence can be used to understand when they were made.

There are a large number of inscriptions in the South, especially in Tamil Nadu as compared to the North. Likewise, there are a lot more temples that have survived in the South as compared to the North. However, both regions have quite a lot of images. In the North, loose images from early periods seem to have survived. These were likely associated with temples made of perishable materials. The later images in the North are not as well preserved and neither are the structures that housed them. Hence the context (the reasons due to which they were made and the form of the images and the structures), is difficult to understand. In comparison, in the South, many, if not most images are fixed in nature and associated with temples. It is thus possible to stylistically date these images and understand the context. Thus, in the South one can determine the context & history by using both inscriptions and the images. Architecture adds one more dimension in the axis of time and hence enhances our knowledge of history. The Sthala Puranas help fill the gaps in our knowledge gained through the material culture. These should not be taken to be sweeping generalizations, as there are places in the North where the materials are well preserved and, in some cases, better than in the South. Overall, though the state of preservation can be said to be better in the South. To a degree, it is easier to conduct surveys and archaeological research in the South. If a combination of all the available materials, together with the ancient texts are used, much greater insight can be gained; this is referred to as an “integrated approach”. The integrated approach requires simultaneously taking advantage of all available “material culture”, including, inscriptions, architecture, iconography (study of images) and ancient manuscripts for researching the topic at hand.

In the case of the Patanjali tradition, texts composed by the Sage himself, such as the Mahabhashya, dating to the 2nd Century BCE are available in their entirety. In the South, several texts that describe Patanjali also go way back in time. Therefore, for the Patanjali problem, it was possible to go prior to the 8th Century CE without excavation. This will not be possible in all cases and hence excavations are absolutely essential to illuminate the ancient Period, i.e., prior to 5th -7th Century CE. This cannot be emphasized enough. There have been quite a number of archaeological surveys and excavations in North India and in South India by the ASI and they have shed light on several aspects of India’s ancient history. These need to be continued, while simultaneously expanding the archaeological investigations in Southern India.

Brief mention is made of some notable, recent historical surveys and excavations in the South Deccan by ASI. State Archaeology Departments also carry out excavations in their respective states and these have also been touched upon next. In general, excavations have been focused on the prehistoric period and the Early Buddhist eras. The emphasis on the Historical Period has been quiet less in the South Deccan.

Excavations conducted by ASI at Gottiprolu, Andhra Pradesh (90 Kilometres North-East of Tirupati) in 2019, revealed existence of a fortified township and trade center dating back to 2nd-1st Century BCE, or a bit further out in time. It appears that people of this township took advantage of their strategic position between the Swarnamukhi river and the ocean to effect their trade. An interesting find from this place is a Pallava-period Vishnu image. The area seems to have been inhabited from the prehistoric period, through the Satavahana, Ikshvaku and the Pallava period. A cavern which housed a Buddhist monastery of the Satavahana period (c.1st Century CE) was found during a survey by ASI in Rudragiri, Andhra Pradesh (South of Guntur) in 2023. Rudragiri was already a well-known prehistoric site, where rock art had been discovered earlier, together with murals from the Kakatiya period.

Brick Fortification Wall Revealed by ASI Excavation, Gottiprolu, Andhra Pradesh. Photo Courtesy: Press Information Bureau, Government of India.

Phanigiri, an ancient Buddhist site has been repeatedly excavated since 1941. This has led to the discovery of a Mahastupa, Chaitayas, Viharas and much more, dating between 1st Century BCE and the 4th Century CE. In 2023-2024, the Telangana State Department of Heritage unearthed a treasure trove of lead coins belonging to the Ikshvaku period. Phanigiri is about 140 kilometres East of Hyderabad. There are many more Buddhist sites at Tirumalgiri, Aravapalli, Nagaram, etc., in Telangana. Along the banks of the Krishna River in Mudimanikyam, Nalgonda District (140 kilometres North-East of Hyderabad) Telangana, two ancient temples were located in 2024 by PRIHAH (Public Research Institute of History, Archaeology and Heritage). These are in unique Badami Chalukya style and date back to the 8th-9th Century. A fragmentary inscription has also been found within one of the temples and has been assigned based on palaeography to the same period.

Until about a couple of years ago, the focus in Kerala was excavating at Pattanam village, which is North of Kochi. Huge number of artefacts including, coins, beads, pottery (both local & from overseas), Amphorae, inscribed potsherds & burnt-brick structures were unearthed. A wharf made of laterite, brick-lining, clay & lime plaster was discovered together with a warehouse. A canoe made from wild-jackfruit wood was also found. The objective was to locate the port of Muziri’s (Mujiri / Musiri), but the study was inconclusive, inspite of it being expansive. In 2024, while digging for a rainwater-harvesting scheme, labourers stumbled upon urn burials at Kundlikkad hill, near Koduvayur village (approximately 58 kilometers North-East of Thrissur). Several microliths too have been found on this hill. The urn burials are possibly megalithic. Besides the large urns (pottery), the capstones were made using ancient tools. The site is unique as it probably straddles several periods. Excavation & research are required at Koduvayur. Recently (in 2025), ASI conducted a survey near the Malampuzha Dam, Palakkad and found 110 Megaliths. These are mostly cist burials built primarily using granite and in some cases laterite. They were constructed by employing large boulders to build the side walls & the capstones (covers). These type of cist burials were common place during the Neolithic & Bronze ages.

Megalitic Cist Burial Site Near Malampuzha Dam, Palakkad. Photo Courtesy: Archaeological Survey of India.

A team of archaeologists discovered 40 Prehistoric sites in Chintamani taluk, Karnataka (about 85 Kilometres from Bengaluru). Numerous artefacts & tools were discovered, including a Palaeolithic burial chamber. A remarkable find was that of rock art depicting bulls, peacocks, elephants, wild boars, and human figures, painted using natural red ochre pigment. The rock art possibly dates from the Neolithic period (10,000 to 2000 BCE). From SDARF’s viewpoint, ASI’s excavation of the “Big Market,” near the Hazara Ram temple, Hampi, Karnataka in late 2024 is interesting. Relying on inscriptions & travelogues, ASI began the excavation at Hampi. This marketplace was renowned for trading of gold, precious stones & pearls. Within couple of weeks, ASI’s initial trenches threw up pottery, a bead and a coin. ASI is partnering with universities & colleges, so that they could expose students to archaeology & excavation. This is an excellent model, as it trains students and more importantly focusses on the Vijayanagar dynasty, which is in the Historic period.

The Tamil Nadu State Department of Archaeology has been excavating at Chennanur, since 2024. The site appears to exhibit cultural continuity through multiples ages, beginning with Microlithic, followed by Neolithic, then Iron Age and finally the Early Historic period, which is unique and indicative of possible continuous habitation from the early period. A polished Neolithic handaxe 6 cm in length and a maximum width of 4 cm was recently discovered at a depth of about half a metre.

As the name suggests, a fort (and a palace) existed at Porpanaikottai, about 10 Kilometres East of Pudukkotai, Tamil Nadu. Excavations have been conducted over the past two seasons (2022-2024) by Tamil Nadu State Archaeology Department and also by the Tamil Open University (in 2021). In 2022-2023, 533 artefacts were uncovered including, a gold nose stud, rubbing stone, bone point (for a weapon), crystal / stone beads, an antimony rod, glass bangle, etc. Within a month of the next season, copper nails, glass beads, copper and iron objects, all totalling 424 were found. Initially thought to be a mediaeval site a hero-stone & potsherds with Tamil Brahmi inscriptions were found, pushing the site’s date to the Sangam Age.

A touching story about a school teacher A. Manickam, comes from the Sivagalai village in Thoothukudi District. Manickam spent years walking around his village collecting prehistoric artefacts strewn on the surface. He built up an impressive collection, but could not attract the attention of archaeologists or the government to Sivagalai, which he felt had great potential for excavations. He built a foundation for protection of the artefacts and in 2018 the media took interest in his collection. Subsequently, the government intervened & excavations were conducted between 2019-2022. The excavations found 160 odd urn burials & numerous iron swords, axes, knives, arrowheads, etc. The charcoal from urns threw up radiocarbon dates of 3345 BCE & 3259 BCE. Ceramic samples were tested using OSL & the earliest sample was dated to 2459 BCE, while paddy remains were dated to 1155 BCE using AMS radiocarbon. These findings have implications for the advent of the Iron Age in Tamil Nadu. Expert archaeologists agree that further excavations & research are required to confirm the findings. Another notable point is the perseverance & passion of A. Manickam. There are several Manickams out there in India, who care deeply about their region or the nation’s past and they need to be encouraged. Read more.

The Tamil Nadu government is giving impetus to archaeology, with a view to understanding the state’s past. An important excavation begun by ASI in 2015 was the one at Keezhadi on the Vaigai River, close to Madurai. Subsequently, seven phases were conducted by the Tamil Nadu State Archaeology Department. Results suggest this was an ancient site, possibly prior to the beginning of the Sangam Age. ASI had initially found 293 sites in 2013 on the bank of the Vaigai. Therefore, several more excavations will be required to understand this culture better. As can be seen from Tamil Nadu, barring a couple of excavations, such as Porpanaikkotai, Keezhadi, most are prehistoric and beyond the scope of SDARF. It is our humble request that more historic period excavations need to be conducted, since it would be easier to trace the history of any given region, given the availability of ancient texts and manuscripts.

As can be observed above, most of the surveys and excavations in the South Deccan are focused on the Prehistoric periods (Megalithic, Neolithic, Bronze & Iron ages). Only a few of the excavations, such as the ones at Gotiprolu, Andhra Pradesh, Phanigiri, Telangana, Hampi (Hazara Rama temple), Karnataka and Porpanaikottai, Tamil Nadu pertain to the Historic period. Gotiprolu was a major trade centre, located between the ocean & the Swarnamukhi River (2nd-1st century BCE), and throws light on trade during that period. Porpanaikottai was initially thought to be an early mediaeval site, however, it yielded a Tamil Brahmi inscription suggesting that the site was occupied during the Sangam Age. SDARF’s opinion is that there are several sites in the South Deccan that can improve our understanding of the Historic period & hence, significantly greater number of excavations need to be carried out at these sites.

Unique Images of Yoga Dakshinamurthy, Pallava-Chola Transition Period, from Thiruchinnampoondi (left). Early Chola, Thirukkattupalli (centre). The Stucco image on the right depicts the unique leg and foot position of this image.